How Nature is Moving Up on the Corporate Agenda

“Any shareholder meeting these days includes questions on what the company is doing about the environment, what is coming in discussions about nature and biodiversity.”

– Alan Lovell, Environment Agency Chair

This sentence was one of my key takeaways from attending The Economist’s 9th Annual Sustainability Week in March in London.

This newer emphasis is due to oncoming and expected disclosure regulations, EU restoration regulations, new frameworks and technologies enabling measurements, increasing awareness of nature-related risks, and corporate commitments to fund restoration or to reduce their operational impact. Although nature is moving higher up the corporate agenda, there are still many challenges for companies to understand to mitigate their impact. But as always, the innovation community is responding.

More disclosures on nature are likely to be mandated. Starting in 2025, the EU will require listed companies to disclose quantitative metrics and targets on their biodiversity and ecosystems impact, dependencies, risks, and opportunities. This is known at the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), which aims to inform investors of the sustainability impact of their investments.

In another big move on nature from the EU, Parliament adopted the EU Nature Restoration Law, which is a legally binding target for member states to restore 20% of land and sea ecosystems by 2030. Although member states voted 329 votes in favour, 275 against in February this year, the law has yet to be adopted by council and officially ratified.

Frameworks are developing, such as the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) and the Science Based Targets Network (SBTN)’s Targets for Nature, where companies have a guideline of how they can measure and report on their nature-related risks and impact. At the event, Emily McKenzie, Technical Director of TNFD, outlined that 320 companies, financial institutions and market service providers had become early adopters of the TNFD framework, with organizations representing over $4T of estimated market capitalization.

It is likely that regulators will mandate nature-related disclosures, following suit of the TNFD’s sister framework, the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD). The numerous TNFD early adopters are a strong signal that these organizations expect this framework to be mandated and they’ve demonstrated an early commitment to transparency, accountability, and a backing of the utility of these frameworks for improved risk management.

Ahead of regulations, companies are already undertaking and funding conservation activities. The Peter Drucker quote, ‘What gets measured, gets managed,’ was repeated multiple times, however, it seems that what is being managed isn’t always measured. Presenting their research on large corporation’s reporting of ecosystem restoration, Professor Jan Bebbington and Dr. Tim Lamont from Lancaster University found that 66 out of 100 of the world’s largest companies carry out ecosystem restoration but only 4 businesses reported monitored ecological outcomes.

Reporting corporate nature restoration efforts achieves three key aims:

- They enable better and thoughtful management

- The accountability builds relationships with stakeholders

- They enable open innovation

It’s easy to draw parallels with the emissions and climate monitoring industries, which have established frameworks, mandatory disclosures, and innovators providing MRV that have experienced exponential growth since 2019. However, monitoring nature is far more complex than emissions with:

- Multiple different environments that need different baselines of what ‘healthy’ looks like

- Many different metrics that can be measured to comprehensively monitor natural environments – these are often different in different environments, e.g., you can use an acoustic sensor to measure the presence, number, and species of whales in aquatic environments, but this would be inappropriate for monitoring different tree species

- Multiple species that contribute to the health of an ecosystem, with the importance of each not equal

- The fact that we don’t fully understand every natural environment, so we cannot accurately determine a baseline, or rank the importance of each monitored metric

Innovators Leading the Way

As complex as this seems, perfect should not be the enemy of the good and many have already developed methodologies and tools to monitor nature-related risks and the impact of restoration activities. For example, Nala Earth has developed a nature monitoring platform for companies to assess the ways they interact with nature, their impact and dependencies, risks and opportunities, and enable target setting and monitoring.

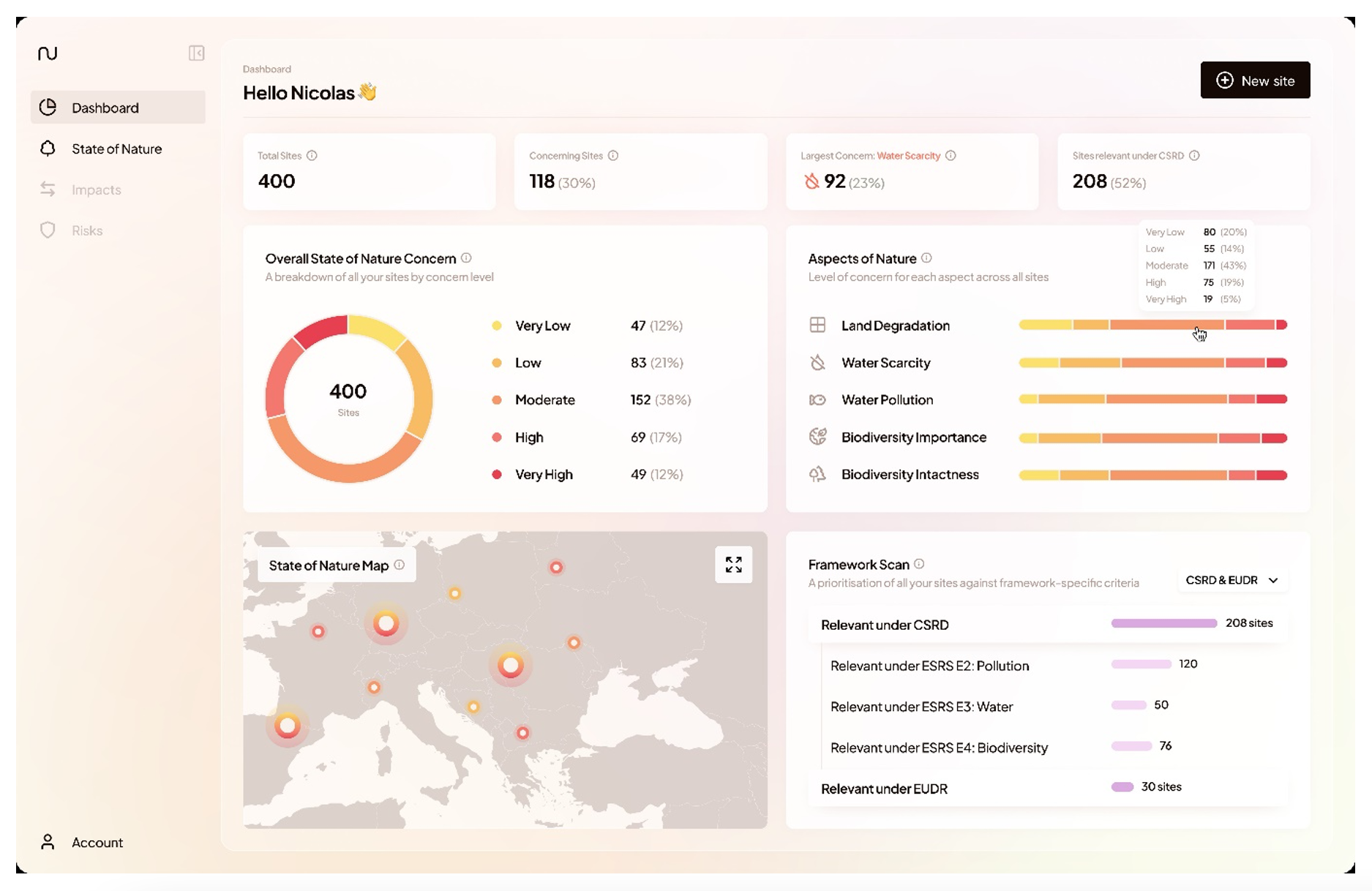

Nala Earth uses multiple primary data sources, such as soil organic carbon as a proxy for soil health, as well as publicly available data sources, such as satellite data, to assess biomass and tree cover. Their value comes from curating, normalizing, and presenting multiple data sources into a comparative, traffic light score on environmental factors such as biodiversity, water pollution, and land degradation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Nala Earth Nature Monitoring Platform Demo, 2024

At Sustainability Week, I spoke with Yoni Pasternak, Chief Commercial Officer (CCO) at Nala Earth, who explained their value proposition: “With investor pressure, real physical risks to business and oncoming regulation, businesses need to come to terms with how they can monitor nature, but lack the data tools and expertise – while carbon and climate tools have been developing for decades – nature tools are rapidly emerging…. We enhance the data for businesses who use our platform for compliance and to form a nature and biodiversity strategy where they can start by prioritizing the most impactful actions.”

When discussing the complexity of measuring nature, Yoni agreed that there are data gaps and that metrics can at times lack the optimal precision but explained, “The status quo now is that companies are flying blind on present nature risks in their operations and supply chain, and these translate into financial risks. The risk of doing nothing is therefore much greater than the risk of using imperfect data.”

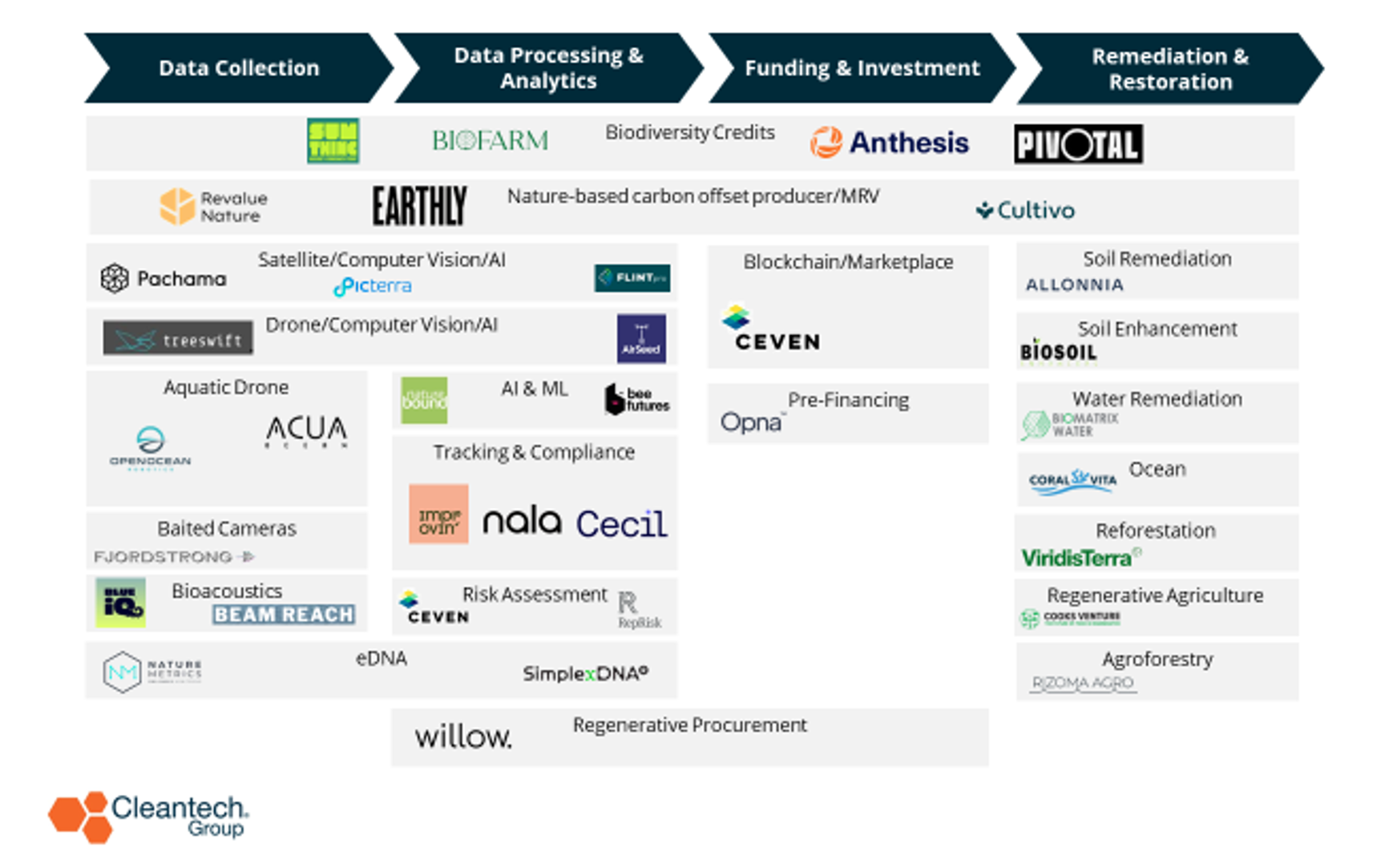

Nature Tech and Biodiversity Value Chain

Cleantech Group has monitored innovators that are emerging across the nature-tech value chain from data collection, analytics, funding, and remediation and restoration solutions (Figure 2). The market is in early stages but developing rapidly off the coattails of the emissions monitoring industry.

Figure 2: Cleantech Group’s 2023 Value Chain for Emerging Nature Technologies

Conservation and nature tech have long been funded by philanthropy or governments; the commercialization of nature restoration isn’t mainstream. The emergence of these innovators is a prime sign this is changing, with new business opportunities in offset markets and emerging biodiversity credit markets.

The escalating prominence of nature on the corporate agenda reflects a paradigm shift driven by impending regulations, advancing frameworks, and growing awareness of nature-related risks. While challenges persist, the burgeoning ecosystem of innovative solutions across the nature-tech value chain signals a maturing corporate understanding of the interdependencies of nature and business.

Innovation also opens new avenues for commercialization of restoration efforts, which opens questions of morality that are too many to cover here. My optimistic hope is that companies are voluntarily embracing accountability of their impact on nature, paving the way for a future where business success aligns with ecological integrity.

I look forward to The Economist’s 4th Annual Sustainability Week U.S., which will take place in NY in June.